Tanoak is thought to be a taxonomic bridge between oaks and chestnuts. Its fruit is an acorn, but with a spiny cap like a chestnut. After the 2002 Biscuit Fire, the old tanoaks started falling, and the old ones started growing, consuming trails.

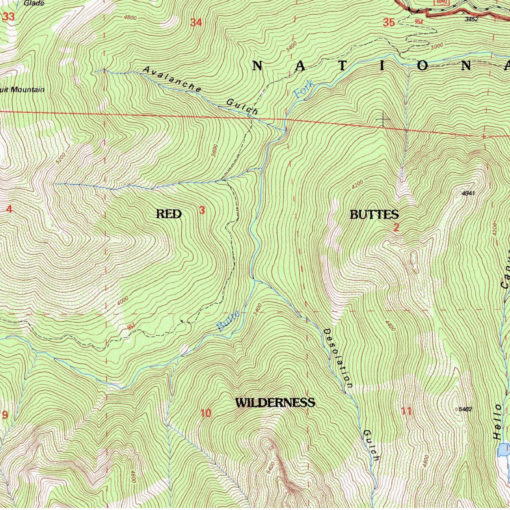

So in 2009, before the Club incorporated, we were clipping it out along the Upper Chetco River, on Bailey Mtn Trail No 1109 just north of Blake’s Bar. Here it had grown so fast and furiously that the trail was unrecognizable.

That year, one volunteer, Tannin, got lost in a brush field of tanoak. Tannin was 23 or 24, he had high cheek bones and these big, bright, bulbous eyes. He kept clipping while the rest of the crew ate lunch.

“Tannin, come on, it’s lunch time,” I cried. But Tannin didn’t show up.

After a couple of hours, we launched a search. Night fell. The next day we searched high and low. But Tannin was gone, lost in the tanoak.

The Club in its infancy, afraid that a lost volunteer would mark the end of our career, decided to leave Tannin out there. The decision weighed on our consciences over the years. We celebrate the fact we have had no accidents. But we never told the truth about losing Tannin.

Last spring I started having dreams about Tannin. What had happened to him? Was Tannin dead? Later that summer we learned he was not.

Over the years, the section where Tannin was lost had grown in with tanoak again. As we worked there, my conscience weighed even heavier. I’d leave the group periodically, in search for Tannin’s skeleton, which I was convinced was somewhere near.

“What’s wrong, Gabe?” one volunteer asked as I returned to work.

“Oh, nothin, just–. Oh it’s nothin,” I responded, nervously. “Don’t leave the trail. People get lost out here.” I could see my volunteers eyeing me strangely.

Later that night, camping at Blake’s Bar on the Chetco,we heard some stomping around.

“Maybe it’s a bear,” said Angie Caschera. Its steps grew closer. We could tell it was big.

We shined our lights across the river, revealing movement in the brush. It was huge, whatever it was. Suddenly the beast appeared — half man, half plant.

It was 15 feet tall, with branches protruding in all directions. Two of the branches were large, four inches in diameter, and at the end of them were long-armed loppers. Its head looked like a giant tanoak acorn, but with a mouth, ears and eyes — big, bright, bulbous eyes.

High, pronounced cheek bones shined through. The beast was Tannin.

He jumped across the river, crashed into our campsite. I looked down, ashamed of our decision years earlier. What had happened? Tannin explained.

“That day, back in 2008, I can’t believe you left me here, Gabe,” he said.

I told him how sorry I was, and how the decision had haunted me over the years. “What happened that day, anyway?”

“That day, when I was clipping and pruning all the tanoak, I was breathing in the dust. It caked the inside of my mouth, tickled my throat, and I started coughing hard, so hard that I passed out. When I woke up after a couple days, I went back to camp and you guys were gone!”

“I’M SO SORRY, TANNIN!” I interrupted, but I could tell he was eager to continue on.

“I couldn’t find anything to eat out here, so I started eating tanoak acorns. After a few weeks, my fingers turned into tanoak sprouts, intertwined with the only tools I had, long-armed loppers.” He lifted his left limb, revealing the clippers. “I made my way through the brush-fields, clipping the tanoak. That winter, after you left me here–“

“I’M SO SORRY,” I sobbed.

“By the end of the winter I had been completely consumed and transformed by the tanoak,” he went on.

“Tannin, come back with us please,” I pleaded. “We’ll get you cleaned up, clip away all those spindly branches, treat you to a real meal.” I wanted to bad to make things right.

“This is my home now, in the brush fields.”

So we left Tannin out there again. Half-man, half plant, Tannin the tanoak, still lives along the Upper Chetco River.

The moral of this story is to always wear a bandanna over your face when working in the tanoak brush fields. Or you could end up like Tannin.